ONE

The Attic of 251 Via Etnea

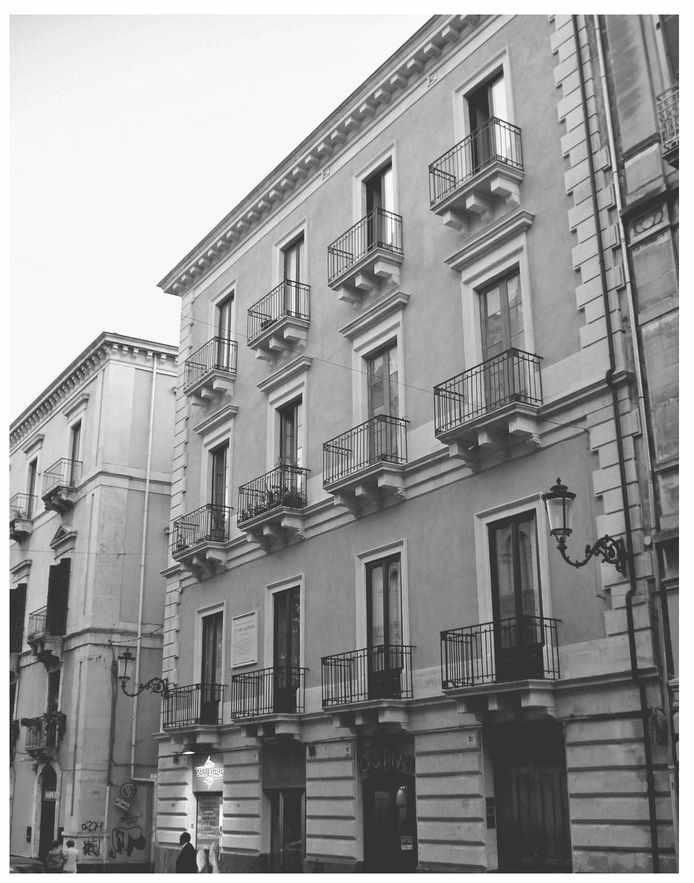

Where to start? For almost two decades I’d been baffled by Ettore’s life, right from day one. So I began precisely at day one: Ettore’s birth, his early days. That’s usually where one finds the magic key to a person’s later life, Freudian intellectual excrement aside. The question, then, was whether the “Rosebud” had already been thoroughly burnt and the ashes hygienically disposed of. I knew where he was born: at 251 Via Etnea in Catania. The top two floors of the imposing building are still occupied by Ettore’s relatives. Before boarding that plane to Sicily, I found the contacts, sent e-mails, made phone calls. Honestly, I’d been fantasizing: Perhaps I would uncover a very aged Ettore hiding in the attic. In truth, I wasn’t taking my chances very seriously: Why would a family carrying such a burden of past tragedy tolerate my intrusion? Still, it was worth a try.

To my pleased surprise, the doors of 251 Via Etnea open up for me. And it’s Ettore’s nephew Fabio, the son of his brother Luciano, who invites me in, leading me to the top floor for a chat. I can’t quite believe my good luck—and I soon realize that things will likely be dramatic even if I don’t discover Ettore in the attic.

At that moment, however, a terrible thing happens. All my previous sojourns in Sicily had been spent organizing conferences, ordering beer, chatting with locals . . . and I got by with working, if uncultured, Italian.5 Suddenly, an appalling realization dawns on me: My Italian is entirely limited to the present tense. I’m João the Pastless—so how will I discuss Ettore? Should I just ask, “Is Ettore in the attic?”

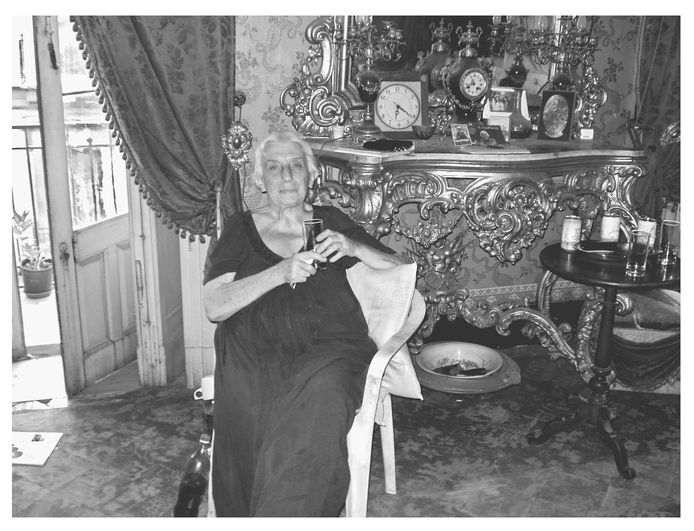

Signora Nunni Cirino Majorana, holding court at her house in Via Etnea.

Undeterred, I converse with Fabio, using the most risible parody of his beautiful language. Remarkably, he doesn’t laugh, even though at times it’s obvious he’s exercising considerable self-control. He takes me to the apartment where his mother lives, into a room full of red draperies, luxurious in a style that’s at least a century old. I’m told that the furniture belonged to Ettore’s maternal grandmother, who occupied the lower two floors of the house until she died. Sitting by the window is Signora Nunni Cirino Majorana, Ettore’s sister-in-law, the last surviving member of his generation. When we enter, the signora is dozing, but she quickly wakes to greet us, evidently happy to have a visit. The signora is an old-fashioned, stylish lady—they don’t make them like her anymore. She carries her eighty-two years with unequivocal dignity, a powerful twinkle in her eye, her wits still very much about her:

“I’m old and a bit of an invalid, but I have a fondness for life that has never been any greater. I love living!”

She pretends not to notice how exuberantly bad my Italian is:

“Signora is displayed like a young rose!”

“Would you like an iced tea?”

When she talks, there’s a sharp clarity to her phrases, an intelligent humor that can’t be far removed from Ettore’s legendary subtle sarcasm. She’s particularly keen to recall her long deceased husband, and it’s via these recollections that I catch glimpses of what Ettore’s family life must have been like.

“Signora wifed a brother of Ettore, Luciano?”

“I did, I did. Ah, that Luciano . . . he made me wait for over a year!”

“ W hat age did signora owned at that time?”

“I was very young. And he was almost double my age. Everyone advised me against it, that he was way too old for me. But what did that matter to me? Why should I care? But for over a year I had to wait for him, not knowing if he’d marry me or not.”

“Why he forced you to long, Signora?”

“That was the problem, more than his age! He said he couldn’t do that to his mother; be so disrespectful, so tactless. I recall he even said that he couldn’t be so cruel. . . .”

“But he was olded fifty years!”

She smiles (that beautifully mischievous smile!) the way she does when she thinks that silence is more eloquent than words. She makes a gesture around her lips signifying that they shall remain pursed.

“But in end he husbanded you.”

“ Yes, I waited for him.”

“ Was it worthed?”

That permanent shine in her eyes redoubles in intensity.

“Yes, it was well worth it! Every little bit.” And then, as an afterthought, “His mother, Dorina, was a tough lady.”

It’s now Fabio’s turn to talk:

“Grandma was good, had a very generous heart. But she was also very tough! No one argued with her: You just did what she said. When I was a child, she terrified me. And, naturally, she also terrified her own children.”

The signora smiles, vaguely. Fabio lights up his pipe.

“She was a woman who knew she had to command for the family to move forward. She was full of initiative, of good sense, but with that she could also be overly protective.”

He takes a drag. A beautiful fragrance fills the room. From outside comes the standard Italian racket of ambulance sirens, motorini, human chaos.

“It’s true that her husband and children were useless with practical things. None of them, including her husband, could find his backside with both hands. But the fact is that she never accepted that her children would grow up. For her they were always children. She bought them pajamas; if they needed money, they’d ask her . . . and this, with sixty-year-old men!”

“I perused that Ettore lifed with mother until the year before his disappearance.”

“That’s right.”

“She buyed him pajamas too?”

“Of course.”

“How did mother react when she heard of his disappearance?”

There’s an embarrassed silence. I realize I screwed up. But the signora finally says:

“Years later, how often I heard her say,”—her voice gains a threatening tone, mimicking what must have been Dorina’s voice—“‘When that Ettore returns, he will hear me!’”

Ettore’s mother never believed that he died, it turns out. When she passed away at the age of ninety, many years after Ettore’s disappearance, she left him his share in her will. Regardless of how much Ettore would “hear her” when he returned, the prodigal son would likely have been quickly forgiven. In Italy, Fabio tells me, you are officially declared dead if you’ve been missing for a couple of years. By the time his mother died, Ettore had been “officially dead” for well over twenty years.

I decide to go for the jugular, to plunge into what could be the “attic” where Ettore is hidden:

“Did Ettore have a strong impulse to evade away from his mother?”

This time, there’s no embarrassed silence; the reply comes at once. “Fortíssimo!”

That was Fabio. The signora is nodding.

The next day, in the local paper, I read about an altercation that happened in Caltagirone, not far off. A very elderly lady confiscated her sixty-one-year-old son’s keys, cut off his allowance, and dragged him to the police station because he stayed out late at night. At the station, the son protested that his mother didn’t give him a large enough allowance and didn’t know how to cook. “My son doesn’t have any respect for me,” the lachrymose lady was quoted as saying. “He doesn’t tell me where he’s going and returns home late. He hates my food and keeps on complaining. This can’t go on.”

The police helped them make up and they returned home together, with the son’s keys and allowance restored.

Ettore was born in Catania, the second-largest Sicilian city after Palermo, with Mount Etna, one of the most active volcanoes in the world, looming in the background. Recently, the volcano has managed massive eruptions every three to four years, with minor affairs almost every year. (The cable car that goes to the top is one of the most expensive in the world: It has to be rebuilt every few years.) The eruption of 1669 reached Catania, almost twenty miles away, the lava filling its port and devastating the town. The city was resourcefully rebuilt in lava stone, its gorgeous baroque buildings now sporting a surreal dark gray hue. This would have lent it a heavy atmosphere were it not for the brutal Sicilian sun flooding its squares and avenues. Beyond the buildings, one can see Mount Etna smoking menacingly, but the pedestrians are far more worried about surviving the hysterical traffic.

Like everyone at the time, Ettore was born at home. A plaque, paid for by the Lions of Catania and the Etna, commemorates his birth at 251 Via Etnea. It reads, pompously:In this house, on 5th August 1906, was born

ETTORE MAJORANA

Theoretical physicist

His timid and solitary genius scrutinized and illuminated the secrets of

the universe with the blaze of a meteor that too soon evaporated in

March 1938, leaving us the mystery of his thinking

The house at Via Etnea in Catania, where Ettore was born and raised.

Ettore’s mother, Dorina, issued from a very rich family; indeed, that magnificent house on Via Etnea belonged to her side of the family—as did several other houses in Catania, as well as extensive vineyards at Passopisciaro, at the foot of Etna. Ettore’s father, Fabio Massimo Majorana, is famous for setting up Catania’s first telephone company, so the name Majorana used to sound to Catanians a bit like Bell does in North America, synonymous with the telephone. As with all private enterprises, his venture was nationalized by Mussolini in the 1920s. Fabio Massimo received a pittance in compensation, but to sweeten the deal, he was appointed general inspector of communications, a cushy job in Rome. The family moved there in 1928.

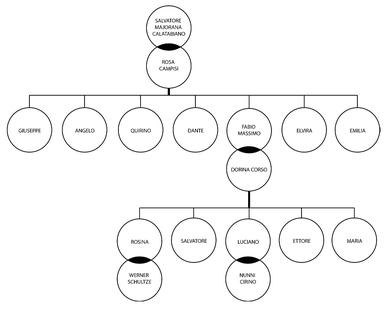

Figure 1.1: A very abridged genealogical tree of the Majorana family, covering three generations. The name of the out-of-family spouse is indicated wherever the branches are followed.

If Dorina’s ancestors bestowed vast wealth upon the family, prominence and political influence came from Ettore’s paternal branch. The family jokes that their unusual name derives from Iulius Valerius Maiorianus, ordained emperor of the Western Roman Empire in AD 457; a jest, indeed, but one not totally divorced from reality, given the family’s uncannily successful and precocious offspring (see Figure 1.1).

The founder of the modern Majorana dynasty was Ettore’s grandfather, Salvatore, a self-made man who, while still very young, became an influential economist, lawyer, and writer, later becoming a member of Parliament; then minister of agriculture, industry, and commerce; and finally a senator. Out of nothing,6 he propelled himself to the summit of academic and political achievement.

Contemporary sources rate Salvatore as a “left-wing” liberal, “the only person capable of unifying the various factions into which the left was split.”7 Other sources portray him as a man who succeeded out of sheer determination and through the power of his intelligence and “despite ancient class traditions and personal interests.” Still others venture that he was “a man who antagonized the old powers, sometimes at a personal cost.” The last reference, I believe, is to a step-son of his who was assassinated. A powerful baron was indicted for the crime and found guilty of ordering the murder, only to be promptly freed.8

After the solid political foundations were laid by grandfather Salvatore, the family successes never ceased to multiply. Salvatore had seven children from his second marriage,9 and it’s rather telling that three of them became rectors of the University of Catania (for the record: 1895 to 1898, 1911 to 1919, and 1944 to 1947). Following the path from academia to politics mapped out by their father, they also became members of Parliament, important public figures, and notable politicians.

One family member of particular note is Angelo, the second of Salvatore’s sons, who was an example of absurd, if not obscene, precocity. Graduating with a degree in law at the age of sixteen, he was appointed assistant professor at the University of Catania at seventeen, publishing his first books the next year, to gain a full chair in constitutional law at twenty. He was appointed rector of the University of Catania at twenty-nine, a record to this day. Joining political life, he climbed to the powerful post of minister of finance in his thirties, to finally conquer the coveted position of minister of treasury, the second most powerful political post in the country.

For all his gifts, Angelo did something tremendously stupid at this point: He set out to solve Italy’s financial and taxation problems (which still plague the country to this day). He soon fell violently ill, dying at the age of forty-four of terminal exhaustion. At 251 Via Etnea, a picture still hangs on the wall showing him at the apogee of his career—on his return to Catania after being appointed minister of treasury, on a carriage surrounded by a cheering crowd.

“I perused that Ettore’s uncle, Angelo, acquired full professorness while aging at twenty,” I say, the Italian language screaming in pain.

“It’s remarkable, isn’t it? He was still a minor; you officially became an adult at twenty-one in those days. When he took up his professorship, his father, Salvatore, had to sign for him because he couldn’t legally do it. Imagine that! A full chair in constitutional law and he couldn’t legally sign. . . .”

“Incredibly precocitous!”

“Yes, but you must realize they had to work extremely hard for it. Angelo and all his siblings,” says the signora.

“I perused that they endured a verily tough regime.”

“Durissimo! All up at six, they worked all day, following a strict plan of studies laid down by their father, interrupted only by the briefest of breaks for meals or to go to the bathroom, working late into the night before being packed off to bed. That’s how the family successes were built. Those children didn’t play.”

“And that’s how they educated their own offspring,” Fabio continues. “Ettore and my father, before they were sent to school in Rome, studied long hours at home under the rigorous guidance of their father. They also didn’t have much room to play.”

We know what effect this had on Ettore—it turned him into a twisted prodigy—but it appears the story was quite different with his brother Luciano.

“My dad was not like the rest of the family, though. He never put pressure on us or forced us to study. He almost never talked of our past family glories. He used to say that as soon as you make children imitate their ancestors you kill their creativity. But in truth, I think he just didn’t want to burden us.”

The signora joins in pleasantly:

“My husband was really kind to the children. None of this nonsense Ettore and those other poor kids had to suffer. He was lighthearted, always playing with them, games, pranks, jokes. Always! It still warms my heart to think of their giggling filling the corridors of this house. . . .” She lowers her voice and her face changes into fake sternness, “Often at my expense.”

“Why, signora?”

“Bah! . . . I could spend a whole afternoon recounting the horrors I had to suffer because of this lot!” She gestures toward an abstract location.

“For example, he’d stuff the kitchen tap with cardboard, then sit with the children until I turned up, and politely ask me for a glass of water, just so that they could all see me getting drenched.”

She’s enjoying her show of indignation (she’s a great actress). Fabio and I are trying not to laugh.

“Another time, when I dozed off in a rocking chair, he made a circle with alcohol all around me and set it alight. Imagine my fright when I woke up! Until I heard them chuckling.”

A few more stories along the same lines are reported, to Fabio’s merriment. I get the idea that Luciano’s pranks were legendary.

“But you liked it, signora.”

“Me? What nightmares did I endure, because of this lot.” She gestures toward the same undefined location. Her face then loses its fake rigidity and she joins us in our mirth. “Ah, my Luciano was so very kind to the children. . . .”

“Papa was a grown-up child,” Fabio sums up.

Later I’m shown Ettore’s and Luciano’s school report cards. By this time they were attending a Jesuit school in Rome: They got marks for things like piety, civility, good behavior, urbanity . . . Ettore got 10 out of 10 in all; Luciano’s card is a laughable parade of 5s and 6s.

“They had very diversified personalities,” I comment.

“Is it too obvious?”

I realize I’m getting an image of the pressures Ettore must have endured by the negative: by learning about the way his brother reacted to those same pressures. In such an austere environment, you either become an anarchist or by the age of four you’re doing cubic roots in your head and winning chess competitions. Ettore’s early successes in chess, by the way, were reported—with awe—by a newspaper of the day.

Of Ettore’s many uncles, I should highlight Zio Quirino Majorana (the third of Salvatore’s sons), who was a physicist at Bologna University and corresponded with Ettore until the end. Today, Quirino Majorana is best known for never having believed in Einstein’s theory of relativity, performing several complex experiments to disprove it. His attitude has been labeled “very Sicilian”: He didn’t care what the whole world thought; he believed that relativity was rubbish, and he was going to prove it. His fundamental honesty then surfaces in the fact that he never failed to report the negative results emerging from his experiments. But he kept on trying, stubbornly.10

Ettore’s father, Fabio Massimo, is the fifth in Salvatore’s remarkable litter, and he was definitely a man haunted by family expectations. But if his own political life was low-key, he was still a very successful businessman, despite being hopeless with money. By all accounts, Fabio Massimo was a disaster with practical things: His wife Dorina took the family reins. He looked after the children’s education, but she collected money, took care of property sales and acquisitions, and kept track of the family’s finances. If anyone needed any money in that house, they’d ask her.

Between such a mother and father Ettore grew up—predictably timid and eccentric, just like his siblings. One wonders how Luciano managed to be such an exception.

But I soon realize that if Luciano and Ettore had very different temperaments, as attested by their wildly different Jesuit-school report cards, they also had a lot in common. They shared a room until the year before Ettore’s scomparsa (disappearance). On their school report cards, they both got 9s and 10s in the academic entries: study, diligence, benefit.

“Luciano was aeronautical engineer?”

“Yes, but he had to give it up. His mother was afraid of him flying and told him to quit. Which he did, unquestioningly.”

“After that, he makes designs for telescopes, no?”

“Yes, he designed the solar telescope up on Etna, for example. And another two: one in Monte Mario, in Rome, and another at the Observatory of Gran Sasso in L’Aquila.”

“He was a very curious man,” the signora continues, “always interested in problems that might improve technology. For the sake of solving them, never for the sake of money!” she adds, as if she should have disapproved of her man’s aloofness in financial matters; should have, but didn’t.

“Father also prepared one of the first proposals for a bridge over the Messina Strait.” I know what he means: The deep strait separating Sicily from the mainland is more than just a metaphorical chasm between cultures. It’s been said that a bridge straddling it—a common promise made by lunatic politicians—would cost more than putting a man on Mars.

“Let me show you something,” says Fabio, producing a letter from a huge folder. Recognizing it, the signora lets out some heartfelt laughter: “We should frame this treasure and put it on a wall!”

“In 1966, Papa sent Ferrari plans for a new type of car engine. It was built upon an idea he knew well from his days in the aeronautical industry. He’d designed engines for planes, different types of propellers and fuel feeding systems, and applied some of those ideas to cars. Why not? Back comes this brilliant document.” He passes it on to me.

On Ferrari’s letterhead is one of the most arrogant letters I’ve come across, and I’ve seen my fair share of scientific referee reports. Luciano is thanked for his endeavors, which have been well noted by Ferrari. However, he is informed, his contraption evidently could never be adapted to the complex engines built by that company; indeed one doubts that it could be of any practical significance whatsoever. Fabio waits for my inquisitive look before dropping the punch line:

“He’d sent them plans for a turbo engine.”

The signora roars with laughter. Quite a few cars with turbo engines contribute to the din that comes from the street.

Later I find that Ettore’s brother also worked on a prototype for an electrical train, with a similar response: He was ridiculed on the grounds that “such a train would require an electric wire running all the way along the track!” And in his attitude of laughing off the stupidity of the world, I find a common trait between Luciano and Ettore. They’d both get 10 out of 10 in “suffering poorly lesser intellects,” in accepting rejection as part and parcel of originality. Ettore was a cheeky bastard: You can see it from the way he played with Fermi, right from day one, even on his induction day at Via Panisperna. I now see that it runs in the family.

We talk about originality and the scientific establishment, and I’m asked my opinion. I have strong views on the matter, so I manage to talk in Italian for ten long minutes. Listening to the tape, even I can’t decipher what the hell I’m saying. I admire Fabio and the Signora’s patience and politeness—their ability to keep a straight face.

I finally manage to steer the conversation away from my opinions.

“Why Uncle Quirino work in Bologna?”

“One day Papa Salvatore found out that he was dating a girl in Catania. I don’t know how Quirino managed to slip out from his studies, but he did and even seduced a girl into the bargain! Over dinner, Salvatore simply ordered his son to pack, no reasons given, and sent him off to suitably monastic friends in Bologna. Dating girls wasn’t permitted.”

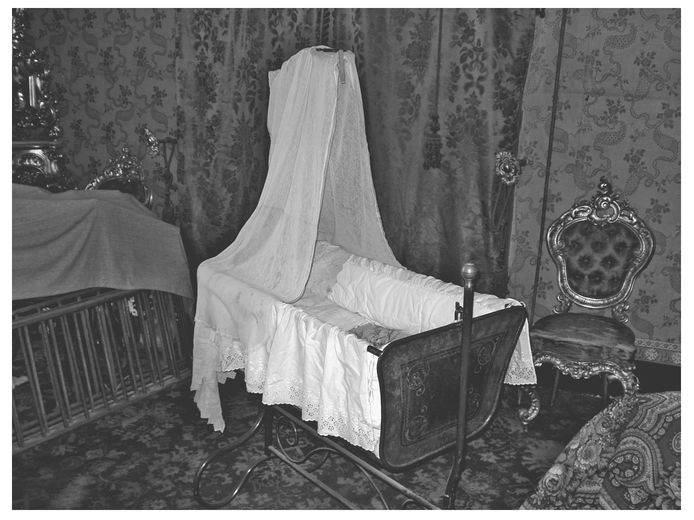

Gradually, I’m getting the picture of this unusual family. We’re obviously talking about a clan with a strong binding energy, where the whole is more important than the parts, and where, during Ettore’s generation, the head, the nerve center, was his mother, Dorina. I’m shown, not without pride, the cradle where Ettore slept as a baby. It’s truly sweet—they used it for four generations: Ettore’s father and uncles; Ettore and his four siblings; Luciano and the Signora’s three children, including Fabio Jr. himself; and finally, as Fabio tells me, his own two children, now in their teens. That cradle symbolizes a bond that cuts through generations. Perhaps for this additional reason, setting fire to a cradle is such an aberration, such a stain. It would be a crime even before it’s mentioned that a baby was sleeping in it at the time.

In one of the nearby bedrooms, Ettore was born. I was born at home, too. Being born at home creates a sense of attachment to a place that’s absent in those who first see the light of day in a hospital. I can sense it at 251 Via Etnea: The house is haunted. Just as traces of urine from several generations pervade that cradle, the spirits of the past have entrenched themselves in the house.

The cradle where Ettore slept as a baby. It has served well four generations of disgruntled geniuses.

“How mother Dorina deaded?” I pidgin along.

I’m shown a photograph of Dorina’s wake, her body spread on a bed as if she were asleep.

“Thus one dies,” says the signora, looking at the photo.

“One day she got home,” Fabio picks up, “and said she felt tired and didn’t want any food. Salvatore and Maria, the children who still lived with her, at once panicked. They called the doctor and told him it was an emergency.”

I laugh. She must have been hard as nuts. My grandfather was just like that. “The doctor listened to her heart, and reported that it was nothing to worry about, she was just tired, that was all. But she looked him in the eye and said, ‘Thus one dies.’”

“Thus one dies,” echoes the signora.

“The doctor left. And two hours later, she was dead.”

Signora is still nodding, as if by considering Dorina’s words, she might be contemplating her own death.

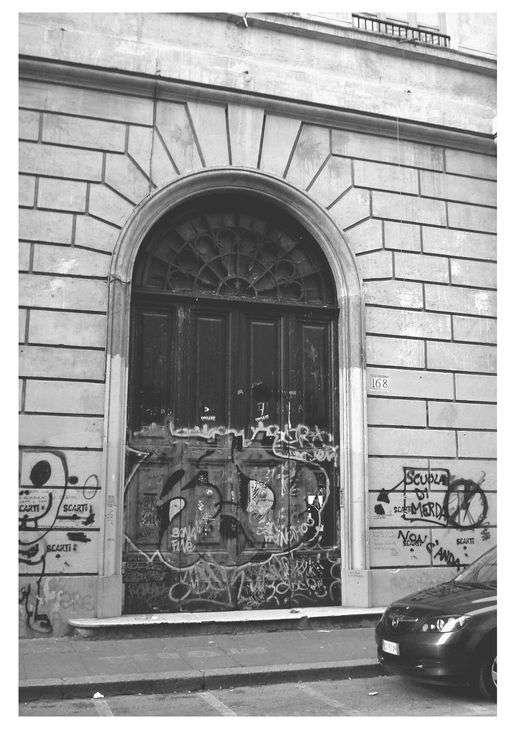

The high school where Ettore studied, today a major grafittiartgallery. Gems include a defense of the right to be stupid and quotes from Epicure, as well as endearing all-out anarchy (“Scuola di merda,” pink flying pigs, etc.).

Instead, Ettore worked on his own at home, when he didn’t while away his days at Café Faraglino or the Casina delle Rose, a delightful place in Villa Borghesa, a large park in Rome. At the Casina, a close-knit group of friends gathered around Ettore: his brother Luciano; Gastone Piqué, from whom he was inseparable; Emilio Segrè; and the “three Giovannis” (Enriques, Ferro-Luzzi, and Gentile Jr.), among others. Over glasses of wine and some serious gormandizing, they conversed endlessly, sometimes discussing science, philosophy, or literature, but more often gossiping as teenagers gossip everywhere, taking the piss out of the world (specifically their hydraulics professor, who they considered a first-class idiot). It

“Fabio, you were the one to answer the phone, remember?”

There’s an awkward silence; he doesn’t take up the lead. I look more closely at him and see that there are tears in his eyes. The signora and I let the silence unroll.

“One night the phone rang, and I picked it up. I was a little kid. It was . . . I forget, it must have been Maria or Salvatore. They told me to go call Papa, that it was very urgent. I ran; Papa came to the phone ash-faced, as if he already knew the news. They hardly exchanged any words. He hung up, and I can never forget what he said at that moment.”

His voice falters. The silence returns.

“He said, ‘Now she knows where Ettore went.’”

For a while, none of us says anything. It’s getting dark, but the heat coming from outside is still relentless. The signora and I let Fabio compose himself. He dries his eyes.

“You see, Papa never talked about Ettore to us. Maybe he felt it was too heavy going for children. But Ettore must have been permanently at the back of his mind. And of Dorina’s mind. Something that silently affected them to the end of their days.”

Looking at the photo of the dead Dorina, with all her children around her, I see the parallel with the cradle they all used through so many generations. Wakes are also times of family unity.

“Strange thing, this one of photographing dead people,” says Fabio, looking at the picture.

Now she knows where Ettore went. . . . This woman who terrified three generations looks calm, relaxed, as if enjoying the most pleasant of dreams.